What Balance Bikes Teach Us About Learning

Our 5-year old decided that he finally wanted to cycle. I confess, I groaned inwardly thinking and steeling myself for the inevitable scrapes and cuts and cries. That’s the rite of passage, right? We got to it with his sister’s old bike and set about practising in his grandparents’ building compound. Five minutes later…he was biking. Pedaling, taking turns without flailing. And all this without training wheels, while proclaiming he was the fastest bike rider in town.

This was his first time on this pedaled bike, but he had been using a balance bike (a light pedal-less bike) for months. It didn’t strike me that pushing himself along on it, sometimes for a few feet at a time without his feet planted on the ground, would translate so easily to cycling. But it did, and in hindsight this makes so much sense that I find myself questioning how we do learning design in general.

Balance bikes were actually the first bicycles around. They were literal hobby-horses, also variously called running machines and dandy horses. These evolved into the pedaled bicycles we now know. Surprisingly, balance bikes did not become starter bikes for people learning to ride bicycles. Instead, training wheels, invented in the 1950s, became the most common learning scaffolds for bikes for the last six decades. Only in the last decade or so have we rediscovered balance bikes and how they are actually better in terms of helping us learn how to balance and countersteer. There’s research that shows us how training wheels actually hinder learning because they lop off our body’s feedback loop.

Here’s a beautiful video from Veritasium about how countersteering works and what would happen if we took away this ability (an ability we acquire unconsciously, because we and our bodies are so wonderful at learning from good feedback loops)

The multi-decade dominance of training wheels is a brilliant example of how the slow creep of complexity in technology and knowledge can often be accompanied by the wrong ways to teach this complexity.

In other words, things become more complex or sophisticated while becoming easy to use for experts or professionals, but not necessarily for beginners to learn them. And our efforts to teach them can actually hurt.

Maths is another great example of this. Here’s my favorite go-to example: How long did it take us to learn that 9 + 5 = 14?

40,000 years. That is how long it took all of humanity to go from tally marks to an efficient notation that can use just 10 squiggles to go from the smallest number to the largest. This is an incredibly sophisticated and efficient notation. But that does not mean it is easy to understand. Our conventional attempts to teach this involve breezily introducing notation and having kids practice carry-over without any understanding of why we use these particular symbols, or what the act of carrying over accomplishes. We lose sight of the greater problem, the problem of quantifying things without dealing with a new problem of creating a very large number of tools (numbers are tools). And that this problem is actually a fascinating journey through time and cultures. We instead focus on the immediate problem of understanding and use. In focusing too much on the how, we lose sight of the why, which could give us meaning, and allow us to design better ways to bridge the gap.

You can see this in that other great tragedy of learning as well. Learning to read. Each year there are articles bemoaning a literacy crisis and declines in reading scores. Consider this NYT article, for instance:

“Their 6-year-old son could not read. He could not remember the alphabet. But he was still being passed through grades.”

How are we still facing these challenges in 2025? With something as fundamental as reading? It’s because of the same systemic pressures and mindset that got us training wheels. English is a highly phonemically irregular language that’s been sculpted by historical evolution and geographical expansion to include all sorts of illogical spelling. There is little logic, only patterns.

Ought (/awt/) we to plough (/plow/) through the tough (/tuff/) terrain of English spelling with patience, kneading the written word like dough (/doh/)?

In trying to make this complexity easy to learn, we end up using the wrong scaffolding. The equivalent of training wheels here is an inordinate and early focus on phonics, on the mechanics, that sacrifices the joy of reading, which really is the joy of imagining and entering whole new worlds. Yes, phonics helps with particular decoding skills, but this cannot come first, before the appreciation of reading and storytelling. (The whole-word approach, on the other hand, is like learning to pedal and balance all at once.)

Balance bikes can teach us a few things about how to arrive at a better solution. First, understand the skills involved. With cycling, it is balance first, and then pedaling. We got this reversed for decades! Second, understand the science of how our brains acquire these skills.

We learn to balance by, well, balancing. It is through the repeated exercising of our motor feedback loops that our muscles and neurons in the cerebellum get trained. There is no book or lecture or video that can replace the act of doing. Training wheels actively hinder this process. With reading, it is from experience, not error, that we learn and discover patterns and perspectives.

We learn because we derive joy from it. Balance bikes still allow for exploration. They do not take away the meaning and joy of the overall activity. They make it possible while stripping away as many things as possible. It’s almost a Zen-like statement: you scaffold by stripping away the excess. Add to learning by taking away the complexity.

This is an important lesson. David Perkins discusses the perils of elementitis, where we encounter complexity and decide to simplify its teaching by focusing on the skills that it is made up of, while losing sight of the overall picture. Kind of like reducing a game of cricket or baseball to a series of monotonous drills. Phonics (alone) or procedural math are pretty much that. Do not sacrifice the joy of exploring, wondering and wandering.

We try to do this, but there’s nothing like a timely and vivid reminder to let us know that it’s easy to lose track while we are focused on the particulars.

Alternative schooling has existed for over a hundred years with this core idea at its center: change learning design for the better. Make it more human and child-centered. We do have Montessori and Waldorf and Sudbury schools, but far too few. This is because it is not enough for a school to change its approach. Entire systems have to be built from the ground up that design for the child first and not the curriculum.

This is what we are trying to do with our work on, as we call it, the full-stack of education: from philosophy and pedagogy to process and practice.

Here are a few examples:

Philosophy & Pedagogy: https://playbook.comini.in/

Process: https://comini-competencies.web.app/

Practice: https://comini-primers.web.app/

In effect, we are diving deep into what balance and equilibrium can look like, while also designing and creating balance bikes for playful minds.

If this is something you are interested in for your children, please sign up here.

Update (13th November, 2025): Bicycles can teach us a whole lot about mechanics and more.

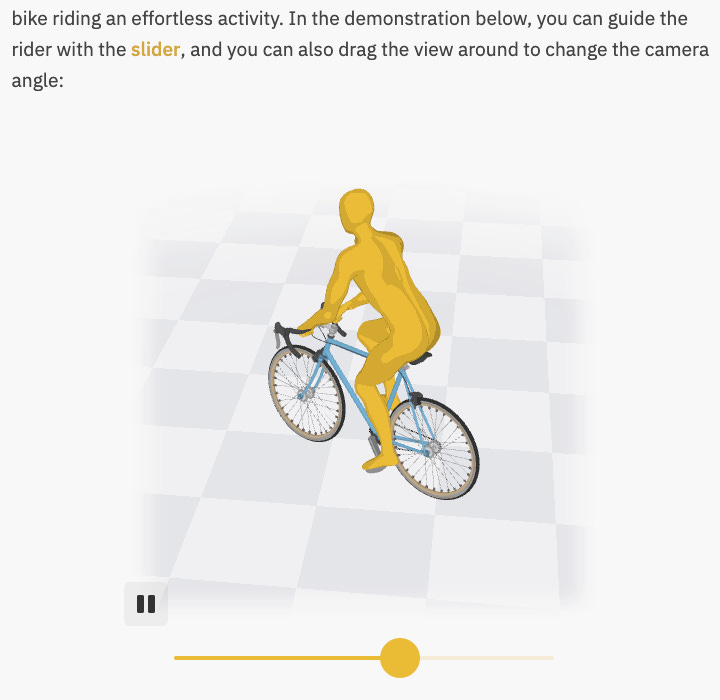

Bartosz Ciechanowski makes absolutely gorgeous interactive illustrations explaining how things work. They are a joy to experience, and a wonderful example of learning design. How to use visuals to break down complexity and also allow one to interact with it and experience it. Here’s another.

I remember in my school days I bugged my teacher as to why giant was not spelled with j and why with g. But we eventually learned. Now I feel that we learned because we practiced reading a lot and that was because no other forms of entertainment existed, so chacha chodhary, chandamama and books were great source of entertainment, we even used to look forward to a small strip of cartoon in everyday newspaper.

Now with all kinds of entertainment, travel, malls, media, games, I really wonder if kids look forward to reading. I really hope that they cultivate interest in reading.