What should replace grades?

Field notes and other useful metaphors for learning

That momentous first day that we enter kindergarten is the gateway to an endless cycle of assessment that will track us deep into adulthood. And all that assessment has a purpose—to measure our progress towards specific objectives set for us by society or by ourselves, such as mastering a subject and obtaining a job.

This quote is not from a book about education or schooling, but one about Artificial Intelligence. It’s fascinating that as we develop sophisticated AI tools, we are discovering unexpected parallels with education. We face the same challenges with artificial minds as we do with biological ones— particularly children.

One foundational challenge in education is the assessment of learning.

What did we learn?

How well did we learn?

It seems obvious that we should know the answers to these questions. Is it?

To answer these questions, and to answer them objectively, at scale, we introduced standardized marking and grades. Someone gets a B in math or a 75 in Hindi. What’s the problem with that? Everything, it turns out.

When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure

We set out to measure how we are doing, and where we are going. Somewhere along the way, inevitably, we lose sight of the goal and focus on the measure. It seems perverse, but history tells us it happens every single time! In the case of education, this is “teaching to the test.”

We set out to educate children, and we end up teaching them to pass exams. And the sad thing is this isn’t even a new revelation. Alfie Kohn called this this out in his book twenty-five years ago. Anya Kamenetz reiterated this under a decade ago in her book. And here’s Ted Dintersmith making a very compelling case for this a few years ago.

We do want to know what we are learning and how we are learning, but clearly grades are not the answer. What is then?

Here’s a preview of how we are doing assessments at Comini. Instead of reductive grades, we do narrative observations. To understand why these make a lot more sense, it’s worth unpacking the metaphors that are implicit in learning and education. In conventional education, you are a box on a treadmill that’s to be graded and packaged and shipped to adulthood. That made some perverse sense in an industrial age, but is woefully outdated now.

Another way to look at learning is through the lens of exploration. We are all explorers in this journey of life and learning. Through this discursive exploration, we learn about the world and our unfolding self. And there’s no goal because these landscapes are infinite. We love this metaphor. We love that we can be guides on this journey. Guides who are there to help when needed, but mainly get out of the way and let curiosity and passion and playfulness take the lead.

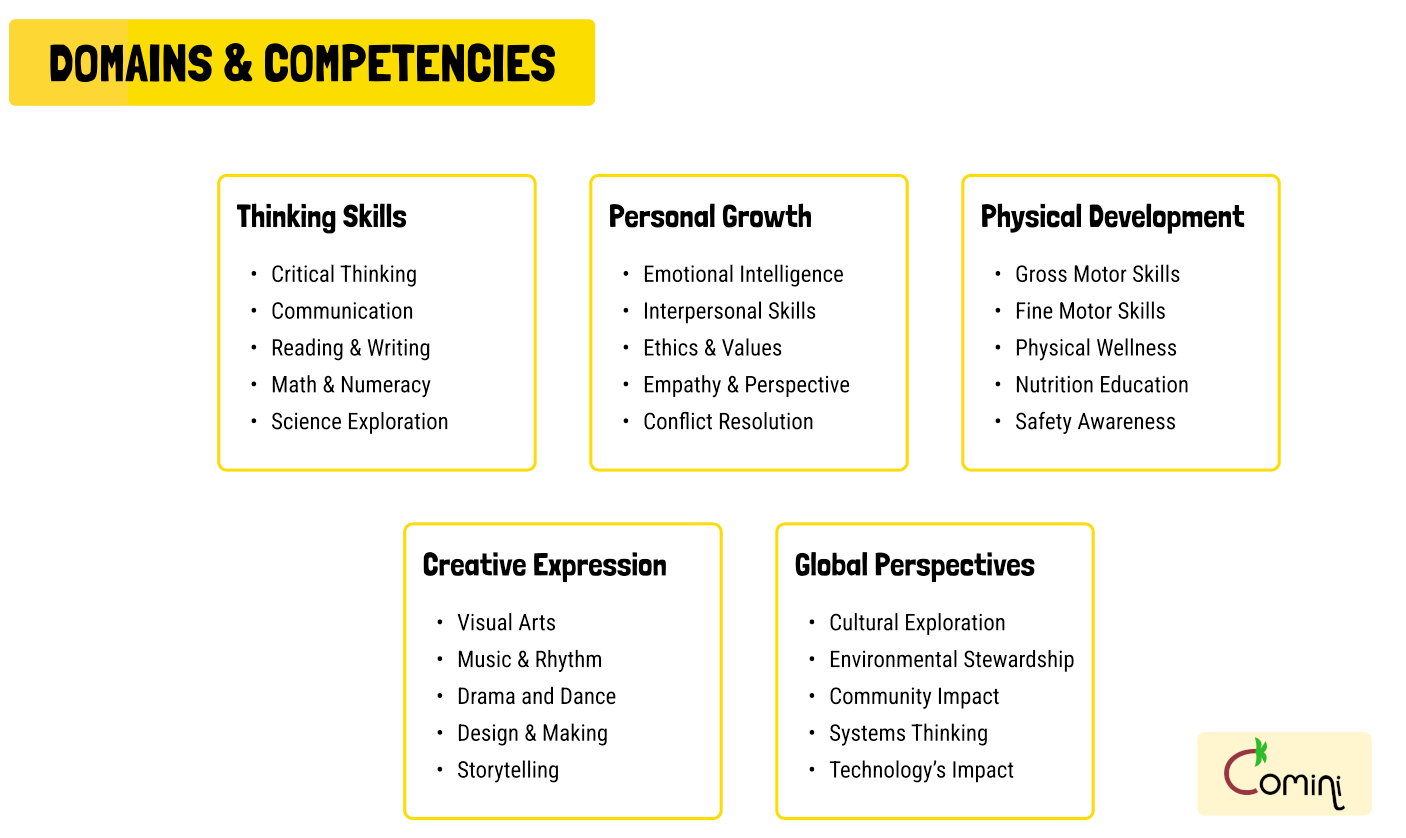

But as guides we can still be well informed. We can use maps to help navigate this journey. We use what we call a curriculum landscape to help our facilitators understand the lay of the land.

We use competency maps to understand what to expect or observe at different ages. We do this with the full understanding that these are broad averages and everyone’s journey unfolds in its own unique way and pace.

So, we have a landscape we want to explore, and maps to help guide us in this exploration. How do we know how these journeys are unfolding? To extend the metaphor, we use “field notes.” These are the narrative observations that tell us everything of note about learning and life along the way.

It isn’t easy for facilitators to create these. To make rich and nuanced observations, one must both see and unsee, and care enough to do those well and repeatedly. That’s another reason standardized grading is so hard to unseat. It is just easier to grade and bin. But these daily and weekly observations are essential and help us all understand and appreciate how learning is multifaceted.

This is actually worth looking at closely. Note how the observation is not about math alone, but the social interactions and dynamics too. And this is hugely important.

Because all learning is cognitive and emotional! We learn because we care for something. Reductive assessments make sure we erase this.

These daily and weekly observations, about individual children and group activities, add up to a pile rather quickly. We use AI to synthesize copious observations made for each child over days and weeks. We built a pipeline to refine and iterate and make these reports a reflection of reality and a truly “intelligent” summary.

AI is quickly making its way into education. There’s breathless hype about AI chatbots, and many parents are understandably worried about handing their wards over to robot teachers. Teachers who drone away in class is one thing, but literal drones? Yeesh.

Here’s where we can again turn to our guiding metaphors to understand how AI fits in. We see AI as a GPS for learning. Maps help us figure out the lay of the land, but maps or atlases can be a literal handful. The older ones among us might remember what it meant to travel to unknown places with a bunch of atlases, poring over pages to find the right one. GPS systems made it easy to figure out how to quickly get to the right map, and to the right level of detail. AI allows us to do the same.

Just as important as what it does is what it does not do. A GPS system does not tell you where to go. Along with maps, they can be used to figure out potentially interesting landmarks and destinations, but the decision is ours. Similarly, we see AI as helping us in many different ways, including synthesizing narratives, suggesting potential areas for improvement, even crafting activity ideas. But where we go next depends on the explorer and the guides. The humans in the loop—the child, the facilitators, and parents—are collaboratively in charge. And when we are collectively on this journey, we bring along the maps, we pay attention to these observations, but we listen to our heart too.

Why Greatness Cannot Be Planned, the book we quoted at the start, ends on this note.

...not only can you trust your gut instinct when it tells you something important is around the corner, but you should trust it, even if you can’t explain what that something is. You don’t need to make up a tortured reason to justify every little impulse you feel. And not only is this attitude more healthy for us as humans anyway, but it’s backed up by solid scientific evidence.

We wholeheartedly agree.